The Call of the Deathbird: The Mystery of Max Schreck

The shadow of the vampire looms large over one of horror cinema's longest enduring classics.

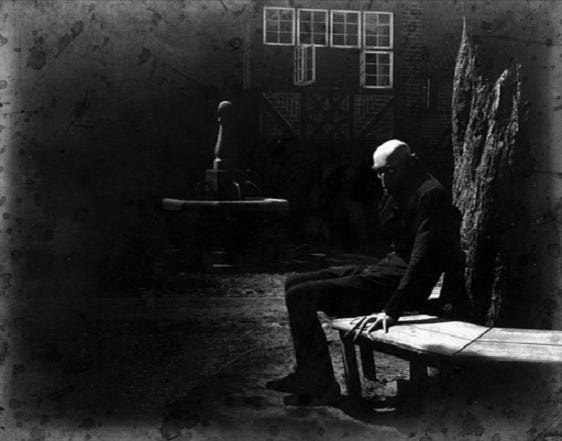

For fans of classic German Expressionist cinema, and particular fans of the horror genre, Nosferatu is one of the most enduring classics of its type. Bram Stoker’s classic novel Dracula is crafted onto celluloid by director. F.W Murnau, with the role of Dracula (or Count Orlock in this production) chillingly brought to life (or the afterlife?) by actor Max Schreck. Even those in contemporary Western society today will know very little about 1920s German cinema, but there is a massive chance that they are familiar with the tall, gaunt, wide-eyed figure of Schreck’s Count. The film is high-drama, very Expressionist - with long shadows and, visual distortion and overwrought gestures, maybe a little hokey by today’s hyper-realistic standards, but there is no denying that Schreck fulfilled his brief, terrifying generations of filmgoers, and still filling film theatres during revivals all over the world.

The film may now place Max Schreck firmly in the spotlight, but we still know remarkably little about him. In all actuality, his performance in Nosferatu totalled nine minutes of screen time, and he was dead by the age of 57, passing away in 1936 from heart failure. The air of mystery surrounding the actor was enough to inspire the 2000 independent movie Shadow of the Vampire, directed by E. Elias Merhige and starring Willem Dafoe and John Malkovich, in which the central premise of the plot is that Schreck, played by Dafoe, is really a vampire. The film was produced by Saturn Films, which is owned by that long-time fan of all that is uncanny and spine-chilling, Nicholas Cage, and Dafoe was actually Academy Award-nominated for his performance as Schreck.

It’s unfortunate to have to myth-bust this hypothesis, but Max Schreck definitely moved within the world of the living. He was born in Berlin-Friedenau, on 6 September 1879, and had to deal, like a fair few performers, with a father who disapproved of his son going into the world of acting. His mother approved of his decision to take up his elected profession, and provided the young Max with a secret stash of pocket money that the budding actor used for acting lessons. It’s only after the death of his father that he felt fully able to embrace his choices and join a drama school.

The young thespian travelled to various places in Germany for acting work, finally ending up in Berlin with the famous Max Reinhardt and then in Munich with Otto Falckenberg. Schreck trained at the Berliner Staatstheater (State Theatre of Berlin), finishing in 1902. It has been remarked that one of the strangest things about Schreck is how little film experience he had before he was recruited to work on Nosferatu by Prana Film for its first and only production. He had worked on one film, a dramatisation of a play called The Mayor of Zalamea, but it was obvious that he had what it took for Prana, when filming got underway on what would become Nosferatu in 1921.

The journey towards release was not an easy one for the Nosferatu team. Murnau was sailing close to the wind with the copyright for Dracula. It was banned in Germany for copyright infringement, coming very close to being lost forever. It was only much later that it was rediscovered and become a classic. It’s easy to see how Schreck’s mystery grew during the intervening years - a banned vampire movie creates that kind of mystique. But contrary to popular belief, he didn’t actually disappear after Nosferatu. He carried on acting well into the 1930s in a range of productions. He married the actress Fanny Normann, though her profile was even lower than his, with a handful films to her credit. In spite of this, Schreck was reported by his intimates to be a ‘strange fellow’ who lived in a world of his own, who loved to take quiet walks in secluded forests in his downtime. The spirit may have been flesh in the end, but some legends, like some rumours, never die. If it pleases us to believe that Schreck was in fact something beyond this world, far be it from us to ruin a great story.